Fault Finding: Mesa de Anguila III

The last day of our Mesa de Anguila trip was spent descending from Tinaja Lujan to the desert floor and returning to Lajitas. Moving in a general NW direction, we followed a series of WNW-ESE-trending, nearly vertical faults in the Terlingua fault zone. The fault with the greatest offset is the Terlngua fault itself, to the north and east of the trail. This fault is responsible for the 1000-foot escarpment that looms over the desert to the northeast of the mesa. The cliffs associated with the faults along the trail aren't quite as impressive, but still prominent. Below you see one such fault scarp, deep in the shadow of the low winter sun. You are looking to the WNW in the general direction of the Solitario in the far distance, the site of an ancient volcano. The cliff is made of Santa Elena Limestone of Early Cretaceous age and is on the up side of the fault. The down side, from the foot of the escarpment and to the right, consists of the Late Cretaceous Boquillas Formation. The topographic relief along the fault is likely enhanced due to the greater resistance of the Santa Elena to erosion.

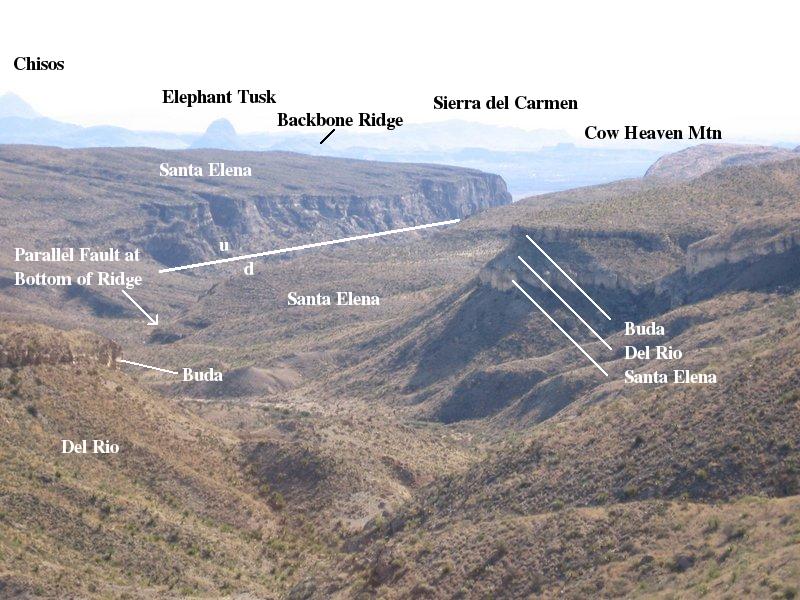

Before we descended from the relative height of the almost horizontal stratum of the Santa Elena above Tinaja Lujan, we caught this view toward the east down a canyon on the east side of Mesa de Anguila. In the distance, you can make out the eastern edge of the high Chisos Mountains, Elephant Tusk, Backbone Ridge, what I think is Cow Heaven Mountain, and Sierra del Carmen. The view is degraded by "forward scattering" due to the low morning Sun. Forward scattering is the physics term, for example, for how you can't see out of a dirty windshield driving into the Sun.

You can't see much of the floor of the canyon due to the ridge underneath the words "Santa Elena". The canyon lies between two parallel faults, although only the trace of the one on the far side can be seen. The ridge on the southwest side of the canyon hides the trace of the fault on the near side. The floor of the canyon has been lowered between these two faults.

Limestone is relatively soluble in water and can, even in the desert, be the substrate for a variety of erosional patterns. The photo below shows the Santa Elena at the bottom of an escarpment eroded into a form reminiscent of an underwater scene. These erosional patterns often make for not-so-happy campers, as they can create very jagged surfaces on rocks you might otherwise rest your weary butt on. We have encountered spots where every rock was like sitting on a bed of nails.

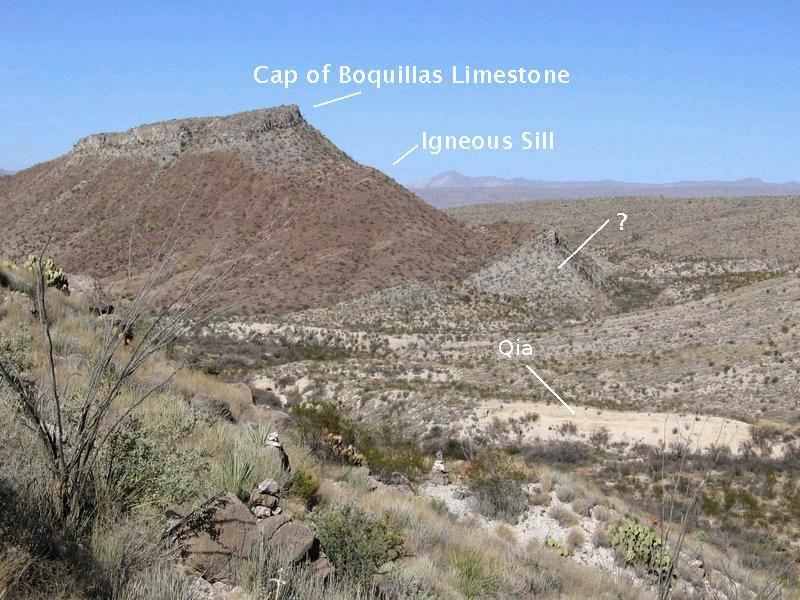

The next photo (looking NW) is of a mesita (a smaller mesa on top of a larger one - in this case on top of Mesa de Anguila) with a cap of limestone of the late Cretaceous Boquillas Formation underlain by a thick layer of intrusive igneous rock of basaltic composition, the sill mentioned in the previous two accounts of our stay on Mesa de Anguila. The igneous rock is easily distinguished from the other rock in the picture due to fact that its iron content causes it to weather to a reddish color.

The rock marked by a "?" was (ahem) a question mark in my mind at the time of the hike, but it is apparently part of the Boquillas Formation as indicated on the new USGS map (Scientific Investigations Map 3142, 2011) of the park. The sill here is rather thick, and I originally thought that it was thicker here than elsewhere on the mesa, but checking it out on Google Earth, I don't really see much difference between the thickness here, at Canyon Flag, or at the Mariposa, two mesitas we observed previously. The fact that the Boquillas on top of the mesita is considerably higher than that at the base probably means the intrusion pushed it up as there are no faults mapped here. The yellow material marked "Qia" are alluvial (water-deposited) deposits of sand and gravel dating to the middle to late Pleistocene, which most people associate with woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed tigers (and maybe neurotic squirrels). Here is a close-up of that deposit. Note the layering, indicative of water deposition.

Farther down the trail is a view across the trace of one of the faults in this fault zone. The rock in the foreground is Boquillas whereas that behind it is Santa Elena. The Santa Elena is older than the Boquillas, so the view is from the down-dropped side of the fault toward the side moved upward. The actual trace of the fault (where it intercepts the surface) runs from left to right on the other side of the Boquillas. The view is toward the southwest.

Although we weren't able to check out the east side of the mesita mentioned above, the wash down which we hiked passes along the southwest side, affording a close-up of the igneous rock, seen in the next couple of pictures. Note the spheroidal weathering of the igneous rock in the second picture. (Also note that the rock hammer is only used for scale in photos, for digging cat holes, and for driving tent stakes in national parks.)

After descending from Mesa de Anguila and crossing the desert, we came to Comanche Creek, which we knew would take us back to the parking lot where we left our vehicle. On our way down the creek we came across what appeared to be an exposure of the Aguja Formation with a very nice example of what geologists mean by strike and dip. The creek bed is a (nearly) horizontal plane cutting the sedimentary beds. Since "strike" is defined as the trend of the intersection of a bed of rock with a horizontal plane, the direction of the rock bed as exposed in the creek is the strike of the bed. The view of the following photo is toward the west, in the same direction as the trend of the bed, so the strike would be E-W. The dip is given by the angle of steepest descent of the bed and its direction is perpendicular to the strike. Since the side of the outcrop in the creek is perpendicular to the strike, the angle of the beds to the horizontal gives the dip, 20° to the north in this case. Measuring strike and dip allows the geologist to figure out what geological structures are present in an area they are mapping.

Finally, as we dragged our sorry carcasses toward the end of the hike, we came across spots in Comanche Creek where water makes it to the surface for at least a short stretch. The creek is generally dry, but water is still flowing below the creek bed, and it occasionally makes a brief appearance before returning underground. Percolation and evaporation of the subsurface moisture is responsible for the salt deposits on the creek bed.

Shortly after this picture was taken, we came back to our vehicle, providing quite a bedraggled, dusty spectacle to some French tourists parked there to view the mesa.

BACKWARD to Mesa de Anguila II

FORWARD to Estufa Canyon

ALL THE WAY BACK to the Contents