The "Basin" is a bit of a misnomer, but when you first arrive there you might think it well-named. You are surrounded by tall mountains, some of which are populated by huge Easter-Island-like rock formations high on their slopes. As on the Grapevine Hills Trail, you may get the feeling you are being observed. These pillars of rock are due to jointing patterns like those at Grapevine Hills.

A basin is a place where water and/or sediment collect. This is not exactly true for this remarkable geologic feature. However, it's almost a basin in the sense there is but one avenue of escape for water that runs down the mountainsides after a desert storm: the "Window". Facing west-northwest, the Window overlook is a favorite gathering spot at sunset for lovers and photographers. (And for my brother, Randy, and me sharing a pitcher of his wife's, Claire's, killer margaritas on our first evening at the park.) See the second image below for the sunset.

The water spills down what is called a "pouroff" (more about these when we get to Burro Mesa) as a waterfall into Oak Creek through Oak Canyon, but this only happens infrequently, usually a few times during the so-called monsoon season. In the view above (pirated from the - apparently now defunct - Basin Webcam on a particularly clear day) you see Amon Carter (left) and Vernon Bailey Peaks framing the Window. You are looking over the pouroff to Oak Canyon, over Burro Mesa, toward Study (pronounced "stoo-dy") Butte. The two peaks framing the Window are due to an episode of felsic (that is, high in silica) igneous intrusion, the Ward Mountain intrusion that occurred approximately 32 million years ago. The dark mountain in the middle distance is Bee Mountain, another intrusion of felsic igneous rock. (This is a different mountain from the Bee Mountain near Kit Mountain inside the park.) Behind Bee Mountain (and difficult to see) is Leon Mountain, which was formed by a basaltic sill), and behind this mountain is the more prominent Sawhill Mountain, a volcanic plug (a mass of solidified lava in the throat of a volcano). The two mountains on either side, and in front, of Bee Mountain are Maverick Mountain (left) and Indian Head Mountain (right). The town of Lajitas and Lajitas Mesa are out of view off to the left. This picture is foreshortened by about a factor of three due to the 3× magnification of the webcam, so that all objects are three times as far away as they appear. (Actually, more like 3.5 times farther away due to image enlargement.) Bee Mountain, for example, is about 15 miles distant.

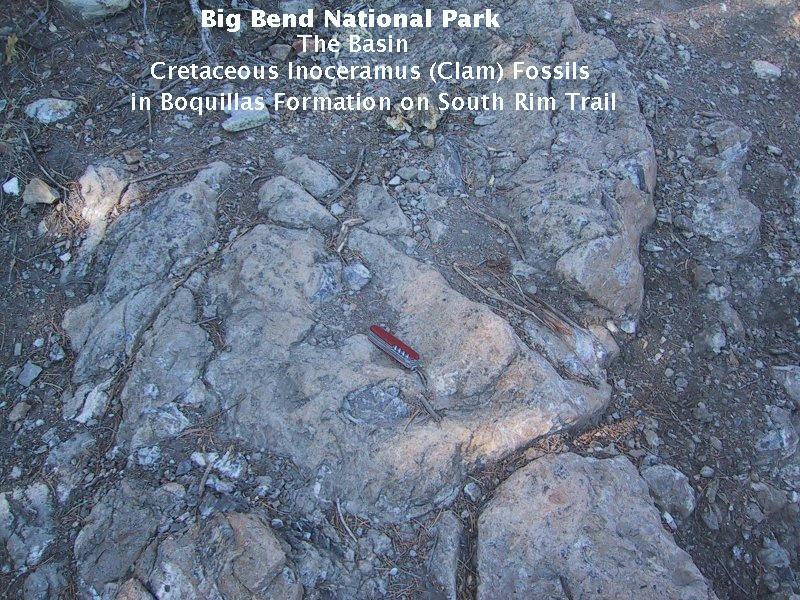

It's morning and time to hit the trail to the South Rim. This is a rather lengthy hike that many like to turn into a two-day event. The trail takes you up the east side of the Ward Mountain intrusion. Everywhere, there is igneous intrusive rock. So as you make your way along the trail enjoying the scenery, you are taken aback when you look down and see, of all things, Cretaceous fossils! (See photo below.)

Had I examined the geological maps before we took off on our hike (I only had the now superceded map of Ross Maxwell, geologist and first park superintendent), I would have seen the green color-coded Cretaceous rock on the map along our route. On the other hand, this made for a delightful surprise discovery: Cretacous Inoceramus clams exposed on the trail. This was like unexpectedly running into a dear friend at a foreign tourist spot. I was familiar with these fossils from their presence in the Cretaceous Anona Chalk of northeast Texas and southwest Arkansas. Here, they are found in the Boquillas limestone. (Note that absolutely no samples of fossils or rocks were taken by us from the park. Not only is this unlawful, but it is an act of great selfishness. Our hiking and backpacking philosophy is, "Take nothing but pictures; leave nothing but doots – well-buried at that.")

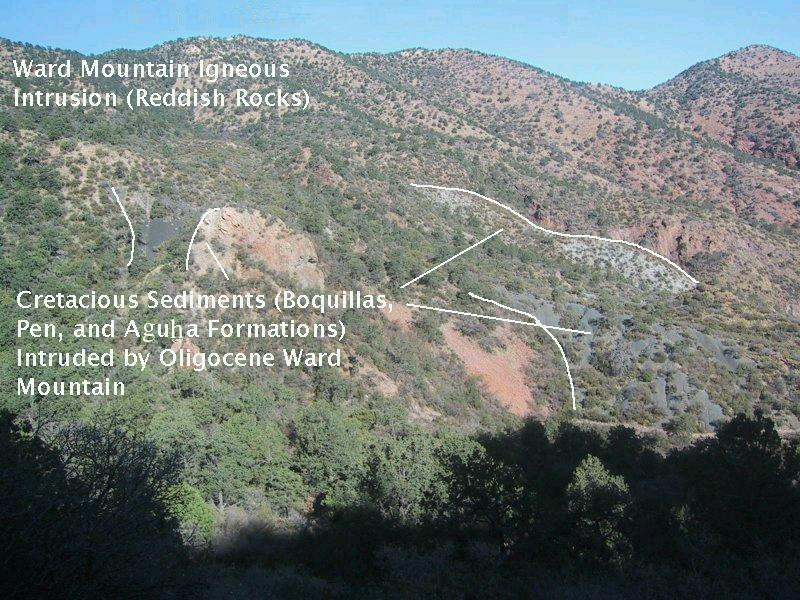

Why Cretaceous rocks and fossils in this igneous setting? The image below helps explain. ("Aguha" in the photo should be "Aguja".)

In this picture you see the reddish igneous rocks of the Oligocene Ward Mountain intrusion but also light and dark gray rocks. These are remnants of the older Cretaceous rocks the magma that formed the Ward Mountain intrusion squeezed into and between. Present are formations familiar from other parts of the national park: the Boquillas, Pen, and Aguja Formations; except here they have been forced up 2000 feet or more by the intruded magma. The scale of the new USGS map (Scientific Investigations Map 3142, 2011) is not large enough for me to be sure about the identification of the Cretaceous units. I originally thought the dark gray rock was the Pen, but the map indicates it is the Aguja and the light gray is the Pen. The Boquillas does not appear in the area of the photograph on the map, but does outcrop to the north along the trail and farther south. Stratigraphically, the Aguja lies above the Pen and the Pen above the Boquillas, but these rocks have probably been significantly contorted by the intrusion.

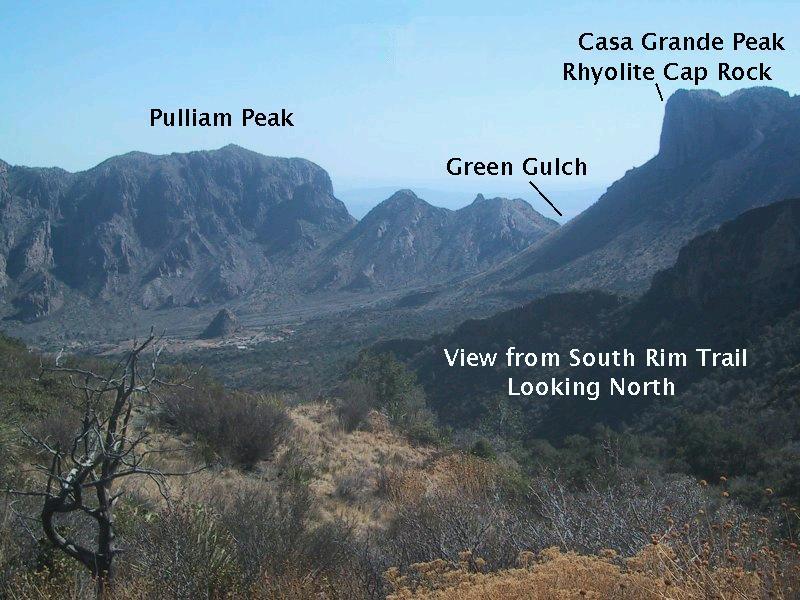

Farther up the trail you begin to gain some altitude and get more of an overview of the Basin. The photograph below was taken as we ascended toward the heights occupied by the South Rim Formation of volcanic origin.

You see another intrusion of the Oligocene igneous activity, 32-million-year-old Pullium Peak. Due to its resistance to erosion, it, like the mountains along which you are hiking, has become a topographic high. On the right, behind the west flank of Casa Grande Peak, is Green Gulch, which is followed by the road that accesses the Basin. Casa Grande is topped by the Boot member of the South Rim Formation - in this case volcanic rock of rhyolitic composition that forms an erosion-resistant cap. In fact, as will be seen later along the South Rim Trail, the Chisos Mountains owe their existence to the protective cover afforded by the South Rim Formation. The Basin was formed where the South Rim was breached by erosion, allowing erosive forces to hollow out an expansive bowl in the exposed, less resistant rock.

This bowl is partly filled with a landslide. Much of the material you are looking at in the Basin is due to a landslide of Quaternary age. It appears to have originated in the Toll Mountain area off to the right. Finally, note the cute little igneous erosional remnant near the center of the photograph, which my brother fondly refers to as the "Nubbin". The Nubbin is in the vicinity of the park development in the Basin and is apparently part of the 32-million-year-old intrusion that created the mountains on the west, north, and east side of the Basin.

FORWARD to the South Rim Trail, South Rim

BACKWARD to the Grapevine Hills Trail

ALL THE WAY BACK to the Contents