Abandoned!: The Geology of Lower Tornillo Creek

I have been fascinated by lower Tornillo Creek ever since my first trip down Estufa Canyon and subsequently reading a paper by Margaret S Stevens and James B. Stevens titled "Carnivora (Mammalia, Felidae, Canidae, and Mustelidae) from the Earliest Hemphillian Screw Bean Local Fauna, Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas" in the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 2003 (which can be found online, by the way). I'm not a paleontologist by any means, but finding a fossil would be a treat: noting the location and reporting it to park personnel. (No taking of fossils from national parks, people! Leave them undisturbed and just take photos.) Then, there are the rocks themselves. Estufa Canyon is on the northern extent of their study area, but I had a hard time trying to interpret the sediments I saw there from their descriptions. Actually, their descriptions were very brief in this paper, but they did publish a number of detailed stratigraphic sections. My main aim in exploring an area farther downstream Tornillo Creek from Estufa Canyon, where a couple of these sections were constructed, was to see if I could answer some of the questions I had concerning the sediments I observed toward the eastern end of the canyon.

I began by hiking down the drainage that contains the Carlota Tenaja. The picture below is of a small fold called an anticline in the San Vincente member of the Boquillas Formation of upper Cretaceous age, composed of sediments of lime and muddy lime deposited in an ancient tropical sea (as Texas was in the tropics at that time). The thick white line marks approximately the "axial plane" of the anticline, a plane which approximately divides the fold into halves called "limbs". Note the thin white line. Imagine it to be the surface above a large anticline for which you have no cross-sectional view as you have here. You could still identify it by the fact the beds dip away from the axial plane. Also note the oldest exposed beds would be in the center of the anticline. Geologists can use these clues to map large anticlines that are not exposed as this one is.

Very quickly walking down from the Old Ore Road, you come across Carlota Tinaja – or, actually two tinajas: an upper and lower one. A tinaja is where water action in a drainage has eroded out a deep cavity in which water can collect. Tinajas are very important for wildlife in Big Bend. In the following pictures you see the upper and lower tinajas, respectively. The rock here is once again the San Vincente member of the Boquillas Formation. Note that the tinajas are near the contact between thinly-bedded, shale-like rock like that of the anticline above and more massive beds of limestone. This is the same situation as at the Ernst Tenaja, which is located at the level of the contact between the thinly-bedded Del Rio Clay overlying the massive Santa Elena Limestone. I'm wondering if this could be a coincidence, or maybe there is something about such a contact that enhances the chance a tinaja could form there.

The Boquillas Formation is noted for its fossils of Inoceramus clam, and many specimens can be seen in the rocks around the Tinaja. One fairly nice fossil can be seen in the next picture.

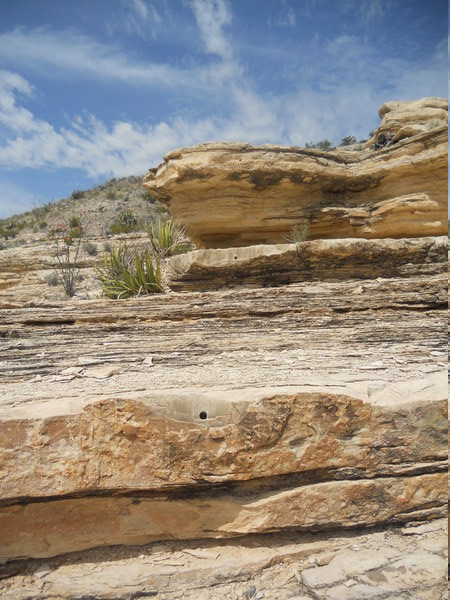

Apparently, geological field work has been done here. In the next picture you can see drill holes where samples appear to have been taken for analysis. If you look closely you can see three holes, all taken at different "horizons" (stratigraphic levels).

As you hike farther down the drainage from Carlota Tinaja, the wash becomes a small canyon with steep walls. On the way back I took the "high road" above the canyon so that I could get an overview. In the following photo, looking northeast, you can see several features. Roy's Peak owe's its existence to an igneous intrusion, magma that never reached the surface, called the McKinney Hills intrusion. Since then, erosion has removed the overburden of material, exposing the intrusion. Like several other exposed intrusions that date about 32 million years ago during the Oligocene epoch – in the Grapevine Hills and the Rosillos Mountains – this was an intrusion of a quartz-poor granite-like rock called syenite. Also in the picture is Alto Relex, a horst, which is an upfaulted block between normal faults. This feature was created during the Basin and Range faulting episode during the past 17 million years and is topped by the lower Cretaceous Santa Elena Limestone. The gray sediments are of the Pen Formation of the upper Cretaceous, mostly lithified deposits of clay with some sandstone and chalk. Although a marine deposit, this sediment was indicative of a transition towards a terrestrial environment as the land rose relative to sea level. The material in the foreground on which I am walking and that resting on the Pen Formation is the Miocene basin-fill sediment in which I was particularly interested. Carlota Tinaja is close to where, visually, the Old Ore Road and the canyon intersect in the picture.

The following was taken farther upstream at the canyon rim. Erosion has cut down through the basin-fill into the Pen and Boquillas (tan-colored rock farther up the canyon). Imagine that you are hiking down the drainage in this picture. In doing so you are hiking "down-dip", meaning you encounter younger and younger rocks as you proceed.

Hiking down-dip means you could come across exposed contacts between the Boquillas and the Pen, and then between the Pen and the basin-fill deposits. The first image below is of the Boquillas-Pen contact, marked by the long, white line. The Pen is typically easily eroded and forms slopes rather than shelves or cliffs. (In the Banta Shut-in area, however, the alteration of the Pen by the heat of the McKinney Hills igneous intrusion has turned it into a metamorphic rock called hornfels, and there it forms steep cliffs bordering Tornillo Creek, narrowing down to the shut-in.) The Pen is largely covered by debris and some vegetation here, but you can see the characteristic gray color, labeled by "1" and Pen debris covering the Boquillas ("2"). There seems to be a fairly sharp contact between the two formations at this location, but I've read where the contact is supposed to be gradational, that is, with the Boquillas transitioning into the Pen. The contact does appear to conformable, however, meaning the beds above and below the contact are parallel, and little time (geologically speaking) has elapsed between the end of the Boquillas deposition and the beginning of that of the Pen. The view is roughly to the north and up-canyon.

The next contact you come to is where the Miocene basin-fill deposits lie on top of the Pen Formation. The line of contact is along the white line on the left of the image below. On the right of the image the contact is covered with debris from the sediments above. This type of contact is called an angular unconformity, where the beds above and below the contact are not parallel. Typically, this type of unconformity indicates a lot of time has transpired between the deposition of the lower and upper sediments, in this case on the order of 100 million years. I take the discoloration as possibly the remnants of the soil that was on the surface of the Pen before the Miocene basin-fill sediments were deposited. If so, the ledge marked could be an ancient caliche layer. Soils "fossilized" in the geologic record are known as paleosols The basin-fill sediments are seen to consist of roughly stratified sand and well-rounded gravel and cobbles, indicating they were deposited by water action. The second image below is a close-up of the contact. The orangish color is either iron oxide or iron hydroxide, or both. This raises the possibility that the soil developed in a warm, humid climate, in which case the ledge mentioned above would likely not be an ancient caliche.

Next, look at a closeup of the Miocene basin-fill sediments a bit farther down the canyon. These sediments, lying right on top of the Pen Formation, have been labeled the lower member of the Banta Shut-in Formation in the work of Stevens and Stevens mentioned earlier. This formation is not yet officially recognized by the geology community and is therefore considered "informal". In this picture you can see cross-bedding with beds containing different sized clasts (sedimentary particles such as clay, silt, sand, gravel, etc.), indicating the currents that deposited the sediment varied in speed and direction. Gravel and cobbles indicate the stream flow was often quite rapid.

Below, you can see what Stevens and Stevens call "Comanche Ridge", although I have yet to see it labeled on a map. This was a major destination of mine as the Stevenses published one of their stratigraphic sections based on the rocks here. However, I was disappointed in that I had a hard time seeing what they saw as indicated in their section. Most of the rocks on the ridge were covered with debris. I could only find a few places where the original beds could be viewed. Another puzzle is that their section is over 60 meters, and the topographic relief of the ridge is 40 meters or less. Since the beds are nearly horizontal here (they dip less five degrees in a westerly direction), topographic and stratographic relief should be nearly the same. I'm thinking that they included observations from the other exposures in the area besides the rocks on Comanche Ridge. Also, they no doubt had substantial time available to find numerous exposures. And, of course, they are professional research geologists, not a "geological tourist" like me. Note the clouds building in the distance. This (April, 2015) was a wet period in Big Bend and the desert was green and full of wild flowers. Also some striking lightning displays at night while we (my brother, Randy, and I) were there. We got rained on three nights out of five! (He went birding while I suffered in the desert.)

It was hard to find good exposures of rock on Comanche Ridge as so much of the ridge was covered with debris. To make matters worse, for some reason a number of photos I took were not recorded. I don't think I yet have the touch for my wife's camera. I really liked my old Canon Elph; never had a problem with it until it gave up the ghost. Plus, it had a view finder, not a screen that is useless outdoors. Complaining over, here are some pictures that did come out. First is one taken at the base of the ridge on the west side – a small exposure of cross-bedded coarser sand over finer sand. Strangely, there was a scattering of high-silica (as indicated by their angular conchoidal fracture) volcanic pieces of gravel to cobble size on the ground in this area.The second is an exposure maybe 10 meters above the base of the ridge. This should be an exposure of part of the informal Banta Shut-in Formation middle member of Stevens and Stevens in which they found fossils of Pseudaelurus, the ancestor of saber-tooth tigers and today's cats (large and small). These sediments are mostly clay, silt, and fine sand. If the ledges in the photo are ancient caliche layers, they may indicate the former location of soils.

There were a lot of interesting fallen blocks around, but too bad you can't easily tell what level they came from. The one in the picture below is interesting because it is an example of graded bedding. This occurs when the water carrying sediment slows down, depositing the heavier material first and then ever lighter material until the flow stops.

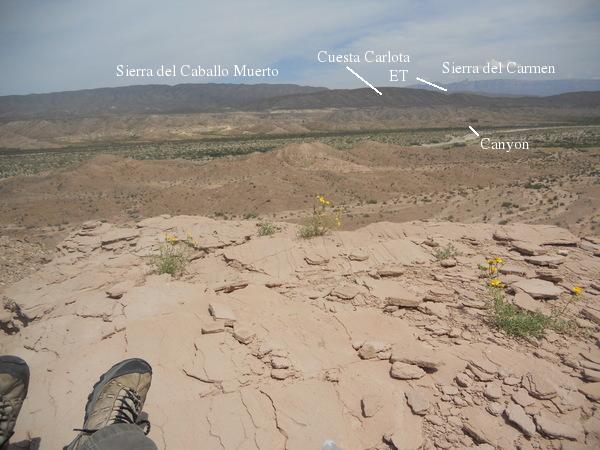

From the top of Comanche Ridge, I took a panorama of vistas. The following is looking east in the general direction of the canyon containing Carlota Tinaja (labeled as "Canyon"). The top of Comanche Ridge should consist of the middle member of the informal Banta Shut-in Formation. Here, it is a well-bedded sandstone. The reddish sediments on both sides of Tornillo Creek should be of the lower member of that formation. You can see grayish and yellowish sediments on the opposite side of the creek that are likely the Pen and Boquillas Formations, respectively. The notch in Cuesta Carlota labeled "ET" is where Ernst Tinaja is located. A cuesta is a ridge that is steep on one side with a gradual slope on the other.

Looking in a northerly direction, you see Roy's Peak and Alto Relex, just barely looming into view. I am not sure of the identification of the members of the Banta Shut-in Formation, but it looks to me as if the middle member may be the more resistant bedding and the lower member the slope-forming sediment. This could well be revised, however. There are two other members of this informal formation of Stevens and Stevens, the red clay member and the bench member. Neither of these are mapped by Stevens and Stevens in this area of Tornillo Creek.

The final vista I'll show is toward the northwest. The Chisos Mountains need no introduction. The sediments marked as Miocene and Pleistocene may not look too exciting, but they have deep, scenic canyons (notably Estufa Canyon) here and there. (The Pleistocene epoch began about 2.5 million years ago and ended with the termination of the last glaciation, about 12 thousand years ago.) The vegetated floor is covered with recent sediments, younger than 12 thousand years.

Heading north from Comanche Ridge, I wanted to check out the sediments lining the west side of the creek and see if I could locate this desert spring that appears on Roy's Peak Quadrangle. According to Stevens and Stevens, this spring is due to a fault. This is reasonable, since a fault can interrupt the flow of subsurface water, forcing it to the surface. In the picture below, taken on the way to the spring, you see an outcrop with slope forming sediments (lower member?) topped by more resistant sediments (middle member?).

The spring was easy to find, but I saw no evidence of a fault. This isn't surprising, since the whole area is covered by recent material and any fault would be buried out of sight beneath it. The new USGS map (Scientific Investigations Map 3142, 2011) of Big Bend shows no fault at this location, but there are undoubtedly many faults in the park that are not significant enough to be on the map. The spring area is heavily covered with vegetation such that the location of the source was difficult. In the next photo you see that a watering tank for livestock was built here with a pipe running from the spring to the tank. It was hard to get a clear picture of both the tank and the pipe. The photo after that shows a little water trickling out of the spring. Most of the water is still underground as you can easily ascertain when your boots sink into the surface on the Tornillo Creek side of the spring.

The final photograph below shows an outcrop of the lower member (?) of the informal Banta Shut-in Formation along the west side of Tornillo Creek.

OK, why is this trip called "Abandoned!"? Luckily, I'm not talking about myself. On the way back to Carlota Tinaja I spotted a weird-appearing object on a small knoll on the east side of the creek. I was getting rather tired at this point and almost blew it off, but curiosity got the better of me, and I hiked over to see what it was. It was a backpack that someone had abandoned years ago. I say "years" because it was faded and inside was one of those 5-hour energy drinks with an expiration date of 2013. The pack had "US" on the back and empty water bottles, but the strangest of the contents were these two smart phones. I didn't want to see if I could haul the pack out myself as I had my own stuff to carry, but I did take some things with me, especially the phones that might help identify whom the pack belonged to. I dropped those off at park headquarters. I also triangulated the position of the pack (I really need to break down and buy a GPS) so park rangers could find it. The problem there was that few good landmarks could be seen from that spot, but I did the best I could. Hopefully, the pack is found so someone else doesn't report a missing hiker. Likely that person got safely out of there, particularly if the individual was part of a military exercise that I understand are often held in the park. But... TWO smart phones? Left behind?

BACKWARD to the Lower Strawhouse Trail

FORWARD to Devil's Den

ALL THE WAY BACK to the Contents