A day of enjoying great vistas and fascinating geology is often best celebrated with a good brew, and, fortunately, the trip to Terlingua through Study ("stoody") Butte features all of this. Actually, my brother, Randy, and I drove to Terlingua ghost town after a trip down Maxwell Scenic Drive to Santa Elena Canyon, and there are only four images for the trip between Maxwell Scenic Drive and Terlingua in this section. After all, a bottle of Sierra Nevada pale ale is best enjoyed while you sit in front of the Starlite Theater and watch the Chisos glow in the sunset before fading into darkness, and time was a-wastin'. Hopefully, I will be able to flesh this section out in the future.

And, delayed though it be, here is the fleshing out. This occurred in May of 2019 when my wife, Nora, and I made a visit to the area. She had never been to Big Bend. To her, being from the Bay Area of California, West Texas looked like "the Moon". However, she did enjoy Big Bend National Park, and was even more impressed with the area after viewing the film "The River and the Wall", which had some glorious aerial shots of the the Big Bend region. I strongly recommend this award-winning documentary.

As Nora and I turned west onto the road to Study Butte after descending through Green Gulch, we passed over a stretch of flatness, shown below looking southwest. She was perplexed as to why there was suddenly this broad area of uniform terrain. This is alluvial (water-deposited) material on the north side of the Chisos Mountains that has the appearance of a pediment. However, the thickness of the alluvium here may mean it would not be considered a true pediment, which is a gently sloping bedrock feature below a mountain range created by erosion and often covered by a thin layer of alluvium. The alluvium here dates from the middle to late Pleistocene according to the USGS map, Scientific Investigations Map 3142, 2011, and the accompanying Pamphlet for USGS map 3142, 2011.

Across the "pediment" to the southwest is a large accumulation of landslide material. There are numerous landslides to be seen in the park. This one could have been a single large event or perhaps several events. I imagine viewing such an event would be awesome or terrifying, depending on where you were. These landslides are relatively recent geologically, dating to the Pleistocene and as recent as the Holocene. Note the hummocky look of the material, which is typical of slumps and slides. Also, since my telephoto function was not working, this and many other pictures in this feature have been enlarged digitally.

The "pediment" has been eroded away such that it has a western edge. As you continue west, you descend a rather steep stretch of road, viewed from the west in the following picture. You are now in an area where there is abundant bedrock. Note how hazy the air is the day I took this and some of the other pictures in this feature.

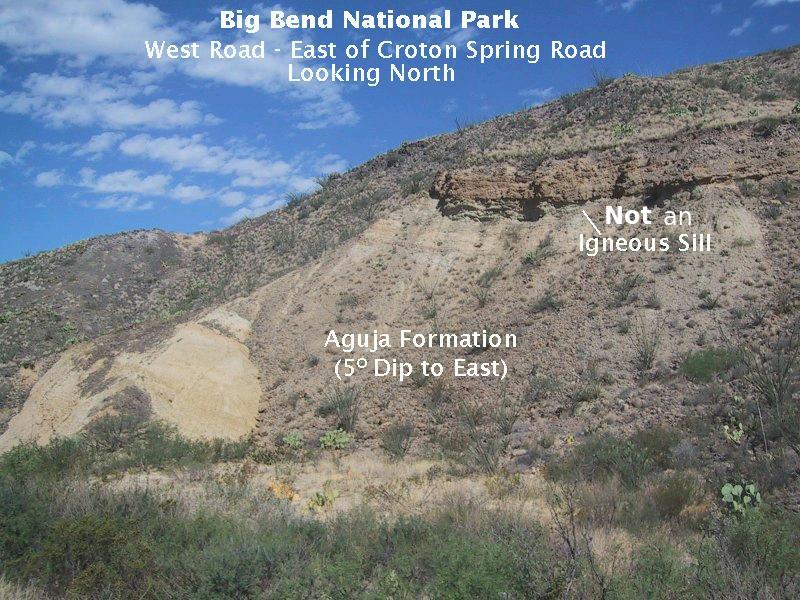

After you descend you come across an outcrop of the Cretaceous Aguja Formation (pronounced something like "a-goo-ha" and is Spanish for "needle"), dipping slightly to the east. The Aguja is late Cretaceous in age and is largely composed of continental clay and sand deposits, although several hundred feet at the base of this formation are apparently marine in origin. Hence, the Aguja records a time in Big Bend's geological history when the sea left the land. Such an occurrence is called a regression.

Penetrating the Aguja at this location - east of Croton Springs Road - is an igneous sill, where magma intruded the Aguja between bedding planes, although whether the intrusion is within the Aguja or not isn't clear to me. After looking at the location where the picture below was taken on this new trip, I don't believe the original labeling of the image was correct. I've doctored the original to indicate the ledge-like feature is not part of the sill after all. The 2011 USGS map, which I did not have then, has been useful. Rather it appears to be a resistant bed within the Aguja itself. However, it is also possible it is Aguja that has been altered due to contact with magma when the sill was formed. Note that this yellow rock is largely overlain by gray-colored material derived from the erosion of the rock above. According to the USGS map, the sill rock consists of intrusive basaltic (basalt-like) rock dating to the Eocene or Oligocene, that is, between 56 and 23 million years old. No specific date is given, however.

The sill is one of many igneous intrusions in the area north of the highway stretching from Panther Junction westward to the edge of the park. Some have the same composition as this one. Others are of rhyolitic composition or, as is the case for the Grapevine Hills and Rosillos Mountains, of syenite. Rhyolite is the volcanic version of granite, whereas syenite is granite-like in composition but with little or no quartz and a higher abundance of alkali metals such as sodium and potassium. You may not know about rhyolite or syenite unless you took geology in college, but most people have heard of basalt, which is high in iron and relatively low in silica. Quartz, for example, would consist entirely of silica were it not for the impurities that result in its different varieties. In syenite, the silica that would have made quartz was used up instead in the making of alkali metal-rich feldspar.

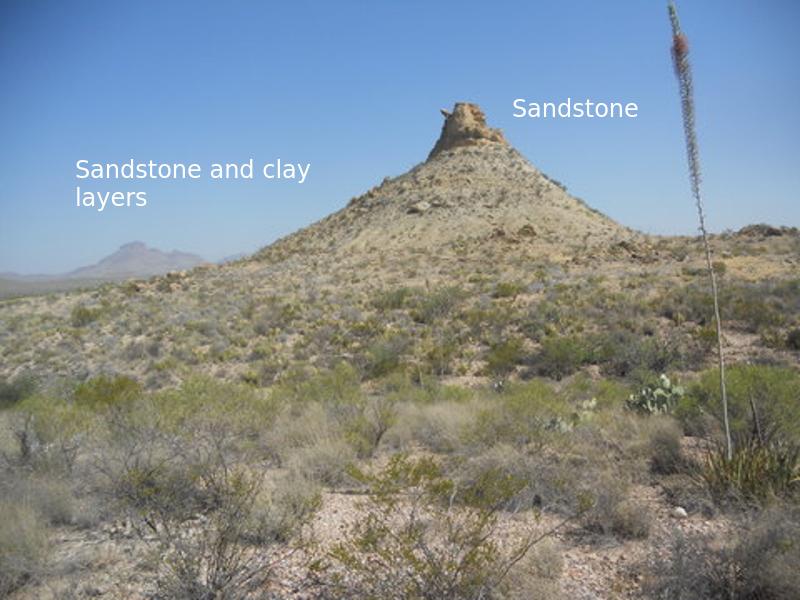

This next image is also of the Aguja, taken farther west on the other side of the intersection with Croton Springs Road. The yellowish sandstone at the top of this erosional remnant acts as a cap rock to protect the rock beneath. On my previous trip here with Randy, I basically presumed that the cap rock was a resistant bed of the Aguja, likely sandstone, but I really wanted to check it out at a future date. I got my chance during the trip with Nora. The remnant looks closer to the road than it is, and you have to negotiate a few arroyos to get there. I took this picture maybe halfway to the remnant.

I made it halfway up the cone-shaped feature before I stopped. I could have gone all the way, but rocks were beginning to slip under my feet, and remodeling of the park by visitors is not something that should be done in my opinion. In the next picture you can see the cap rock – definitely sandstone (as also indicated by broken-off pieces lower down) and appears to have some sparse gravel mixed in with the yellow sand. There was a drama unfolding. A mated pair of white winged doves were being hassled by a bunch of crows and one or two vultures. Likely, the crows were after either their eggs or their young. You can just make out one of the distraught doves on top of the cap rock.

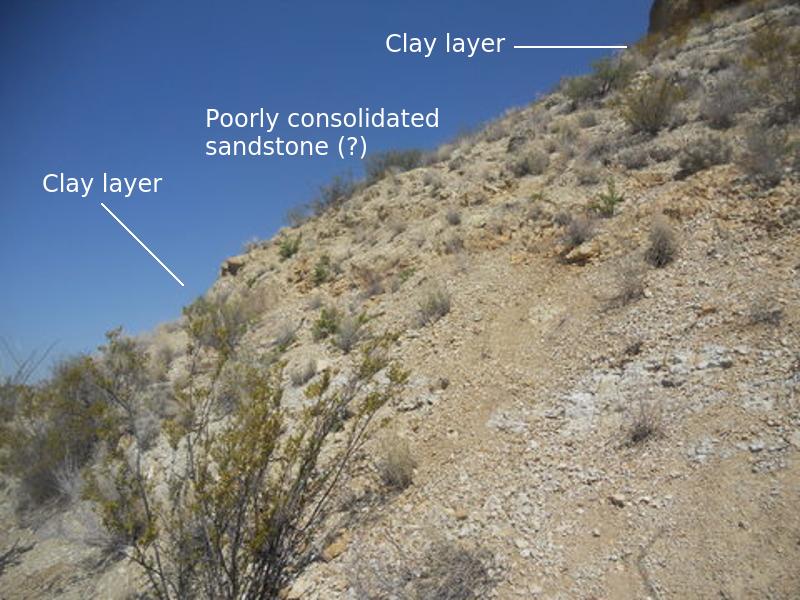

Below the cap rock is grayish clay, then some more sandstone, and another layer of clay, shown in the next image. Hard to tell exactly what was there due to all the debris. Nevertheless, according to the description of the Aguja in the afore mentioned pamphlet, this appears to be near the top of the formation and thus terrestrial rather than marine in nature. You can look around in all directions, but this is the only feature that appears to remain in this area of the Aguja sandstone bed. Once the sandstone cap finally succumbs to erosional forces, the protected rock will quickly disappear and all you will see, standing roadside and looking north, is flat terrain. (But the road will likely also be gone by then.)

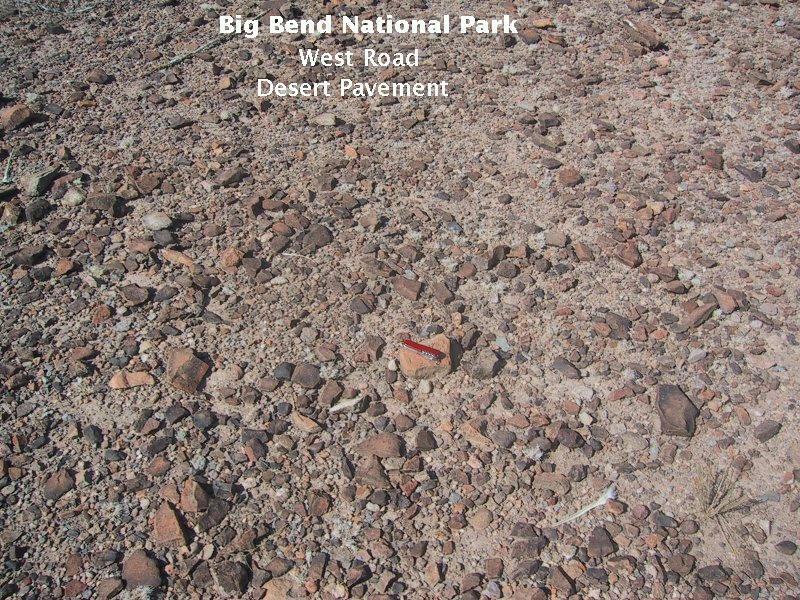

Like much of the desert floor, the surface around the erosional remnant (above) is windswept. Lighter material is driven off by the wind leaving the heavier gravel-size particles. This results in what is called desert pavement, which is ecologically important in that it protects the land from further wind erosion.

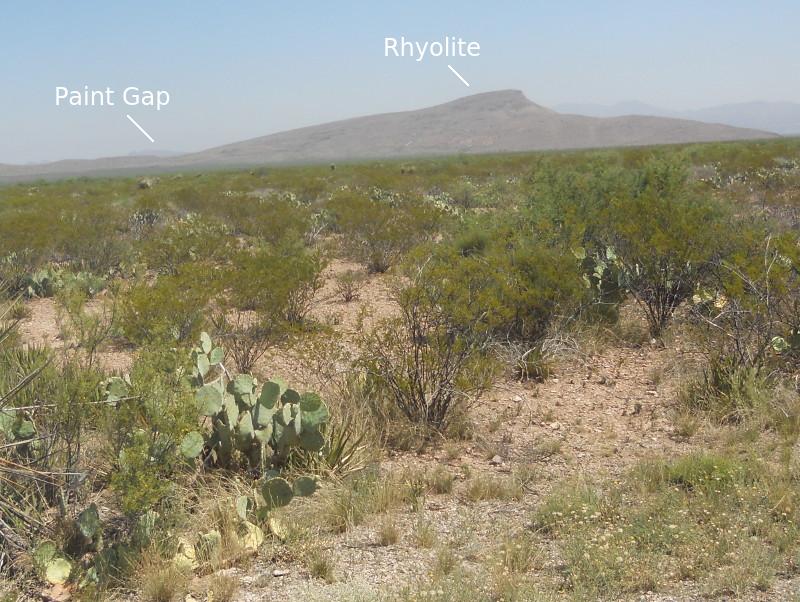

Now we are going to take a look at some of the mountains along the road from east to west. First up are the Paint Gap Hills, topped by a rhyolitic intrusion, apparently a sill. The resistance of this rock to erosion is presumably responsible for the cuesta-like shape of the tallest hill.

Next is Croton Peak, viewed first across the "pediment" in a northerly direction and then from the west. This peak is also topped by rhyolite. This would be the same sill as that of the Paint Gap Hills and Slickrock Mountain farther west, and here there is evidence that the sill intruded the Aguja Formation. At least there is contact with this formation. The ledge of rock in the middle ground of the second image is a section of the same rhyolitic sill. The sill was probably once continuous over much of the area, but is now broken up by erosion.

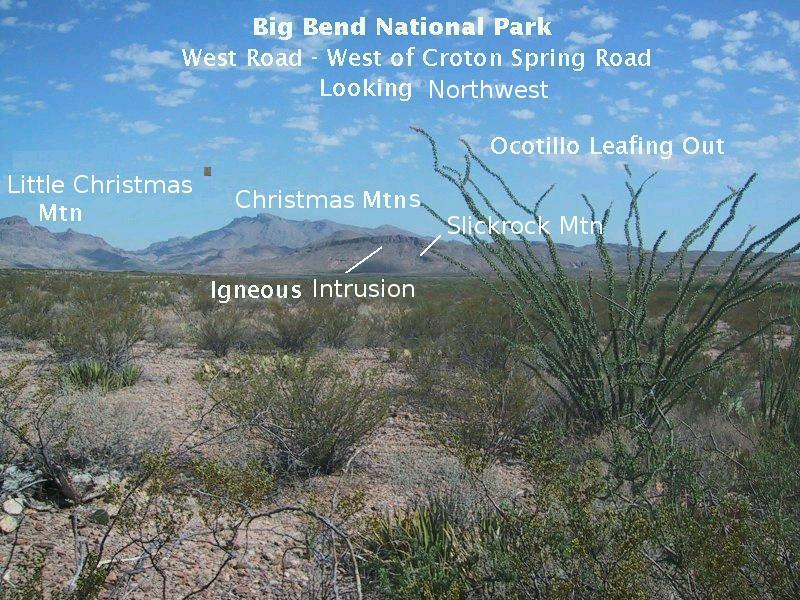

The image below was taken on the previous trip looking northwest toward the Christmas Mountains with Slickrock Mountain in front. In the previous version, I identified it as the erosional remnant of a mushroom-shaped igneous intrusion of rhyolite called a laccolith, but it is almost certainly owes its existence to the erosional resistant sill that is also found at Croton Peak and the Paint Gap Hills. I can't remember where I got the erroneous information it was a laccolith. A radiometric date places the formation of this sill at 31.7 million years ago.

But, speaking of laccoliths, there are numerous intrusions of this type in the northern half of the park, including the not too distant Government Springs laccolith the park road cuts through a few miles after leaving Panther Junction heading west. Little Christmas Mountain is another rhyolitic intrusion. I know of no date for Little Christmas Mountain, but it could be the rock that forms it was emplaced at about the same time as that of the Government Springs laccolith, also composed of rhyolite, 33.0 million years ago.

Note the ocotillo leafing out in the foreground. These weird plants look like pipe cleaners but put out beautiful red blooms earlier in the spring. By May, when this picture was taken (during my previous visit), they begin to put out leaves, apparently in anticipation of the summer "monsoon" season, which is the wet season from Big Bend, south into the Chihuahua Desert of Mexico, and west into New Mexico and parts of Arizona. I've read where the ocotillo leafs out after even a light rain; however, there was no rain that I know of due to a prolonged drought prior to this picture. Possibly a stray shower occurred at this location.

One of the major faults along the route is the one you cross over while cutting south around Burro Mesa. I don't have a picture of the south end of Burro Mesa, so I pirated the following from Google Earth. (Hey, Google! I'm not making a red penny off this!) Unfortunately, the road images from Maxwell Scenic Drive and west are old and of poor resolution, so this picture was taken from a more recent Google photo run that only went so far as the turnoff to Maxwell Scenic Drive. There is a small hill, as you can see, blocking the view to the southernmost point of the mesa.

The dark rock along the ridge of the mesa is the Ash Spring basalt of the Chisos Formation interbedded with other volcanic rocks of that formation. A radiometric date taken just below the basalt is about 42.1 million years and just above about 41.4 million years, so the age of the basalt is between these two numbers.

You can find the fault if you park where the road curves around the south end of the mesa and descend toward the arroyo that parallels the road at this point. The fault is in the arroyo since it is a line of weakness where erosion is enhanced. In the following image you can see the rock on either side of the fault. Not much visual difference is apparent, but the rock on the left looks slightly less reddish and shows spheroidal weathering in spots that I didn't see on the right. The USGS map labels the rock on the left as Tv, volcanic rocks of unknown composition that are Oligocene in age. The rock on the right is of the same type as that on Slickrock Mountain and is likely part of the same sill.

Now you might think the left (west) side of the fault is up with respect to the right side, since you have Burro Mesa elevated on that side, but the topography is deceiving. Just as the Chisos Mountains are on a down-faulted block and stand high as an erosional remnant due to the resistance of their rock to erosion, so is the case here, apparently. To prove the west side is down-faulted, you walk a bit farther down and observe that the Oligocene volcanics on your left are adjacent to the much older Aguja formation on the right. The Aguja is the light-colored rock in the next picture, in contact with the rhyolitic sill due to the sill's intrusion. The Christmas Mountains are in the distance.

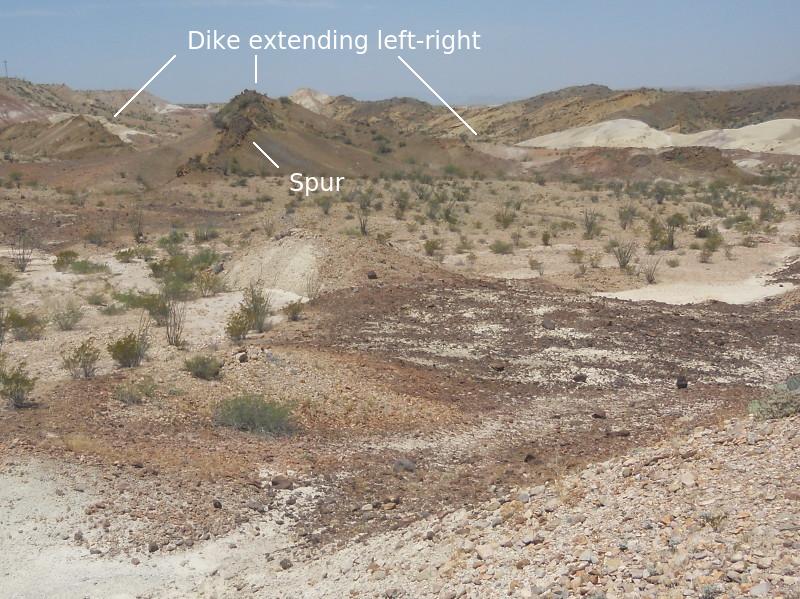

Our last geology stop was just west of Maverick Junction where the terrain has a distinct badlands look. In the foreground, looking westward, is the Javelina Formation, which has been intruded by magma of basaltic composition; the feature labeled appears to be a dike, a sheet-like intrusion that cuts across bedding rather than intruding parallel to it as a sill does. The Javelina Formation is Upper Cretaceous in age and was deposited in a terrestrial (above sea level) environment. I'm thinking the white material in the photo might be part of the middle tuff bed of the formation, 69 million years of age. If so, it could contain petrified wood. The Javelina lies on top of the Aguja, which gradually grades into it. No age is given for the basaltic rock, but it has to be younger than the Javelina and was undoubtedly emplaced during the Eocene to Oligocene volcanic activity in the park.

In the following closeup, you can see the spur that trends from the dike, which extends left-to-right, toward the the camera. (I'm not sure this is actually a dike, but this makes it easier to write about.) Also note the dark-colored erosional debris overlying the Javelina.

The following is a closeup, looking in a northerly direction. The west side of Maverick Mountain, seen in the photo, is not on the USGS map, but certainly must consist of the same intrusive rhyolitic rock as the east side, which is on the map. I'm not sure I can extrapolate the Aguja at the base of the east side to the west side, but I have done so on the photo. It could easily be geologically recent alluvium cut into by Dawson Creek instead, but the Aguja does outcrop around the mountain, having been intruded by the rhyolite.

The last Maverick Junction picture, below, is of the east side of Maverick Mountain. Again you see a couple of basaltic intrusions, including a cute little column-like feature. (Not so little as it looks.) The more distant intrusion rises out of the Aguja Formation.

When you finally get to Teringua, a former ghost town and site of the inter-galactically famous Terlingua Chile Cook-off, you can go into the store adjacent to the Starlite Theater, grab a beer out of the fridge, pay the sweet young thing at the counter, and sit out on the porch with the locals (and a number of friendly dogs) for a fantastic view of the Chisos as the sun settles in the west. The picture below was taken (on the previous trip with Randy, who is credited with the photo) just a bit late to catch the full effect of the sunset. However, I'll have to fess up and admit to doing a little color and lightness adjustment to try to compensate. Helped only a little. Unfortunately, at one point I heard the dogs had been banned from the porch. (Now, y'all know thet jist ain't raht!) On this subsequent trip we saw that the dogs are back! :-D

FORWARD to Maxwell Scenic Drive

BACKWARD to Tuff Canyon

ALL THE WAY BACK to the Contents