The trail to the Chimneys is one of the easiest in Big Bend. Granted, it may be a wee hot in the summer (we did it in June), and you have to watch for the horse-crippler cactus (Echinocactus texensis - I got one through the sole of my shoe), but the trail is well-developed and the topography almost level. A stroll of only three miles gets you there.

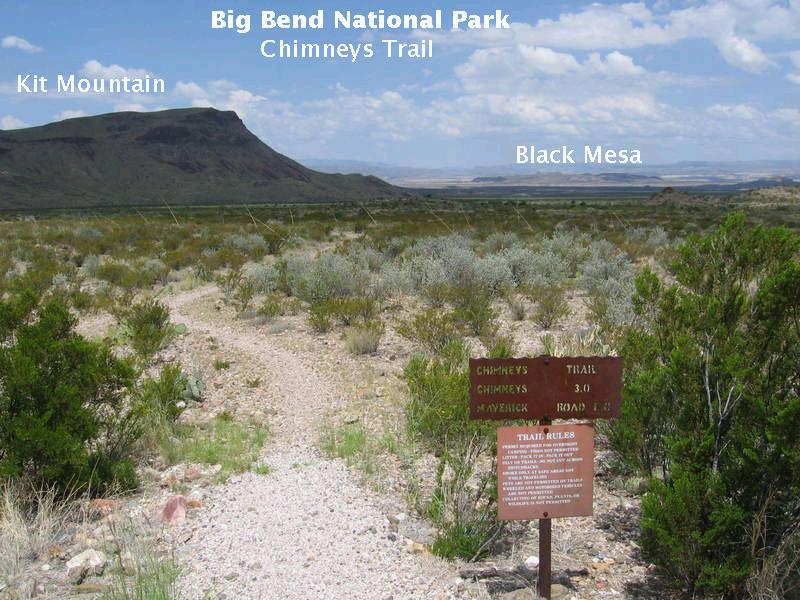

You see, in the image below, the trailhead with Kit Mountain to the left, shadowed by clouds, and Black Mesa in the distance, mostly in sunlight. The view is almost due west. Black Mesa gets its name from the dark Alamo Creek Basalt, which was erupted between 47 and 46 million years ago and forms the top of the mesa. A sample dated radiometrically from the Mesa produced an age of 47.0 million years. In most areas of the park, the Alamo Creek is stratigraphically the lowest unit of the Chisos Formation, but it overlies older Chisos rocks in the Dogie Mountain area. In moist places like Hawaii, basalt quickly weathers to red soil, but it tends to be more resistant in dry areas such as Big Bend. In addition, not all of the Alamo Creek Basalt is actually basalt. It consists of several lava flows, some of which are trachyandesitic in composition, which is a volcanic rock with more silica and alkali metals than basalt. The basalt flows themselves are also fairly alkaline. The Alamo Creek Basalt extends from here north to Dogie Mountain (just outside the west side of the park) and west to the town of Lajitas (just outside the southwest side of the park along the Rio Grande).

(The most interesting thing about Lajitas is that it has had a goat for mayor since 1986. The first mayor, Clay Henry I was killed in a dispute with his son over a female goat. Nevertheless, in spite of that crime, Clay Henry II succeeded his father as mayor. The mayor now is Clay Henry III. The two former mayors enjoyed a brew now and again, but the current mayor is a teetotaler who only drinks Gatorade.)

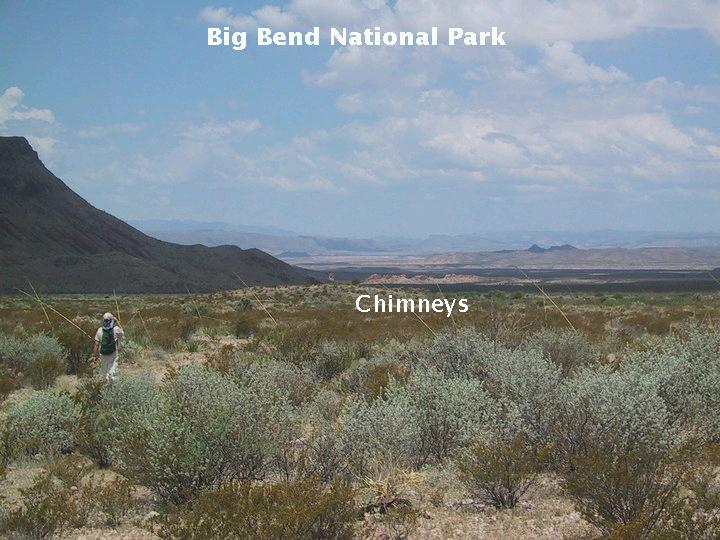

In the picture below, my brother, Randy, is snapping a telephoto just as a swath of sunlight illuminates the chimneys. His photo is displayed in the next picture. (The first photo was also taken with magnification, but not as much as Randy's.) The clouds were certainly welcome due to the heat, even though they did make photography difficult. The Chimneys are about 2.5 miles away at this point, and Black Mesa is several miles beyond that. Note how green the vegetation is. This was in 2007 after an unusually wet spring in West Texas.

.

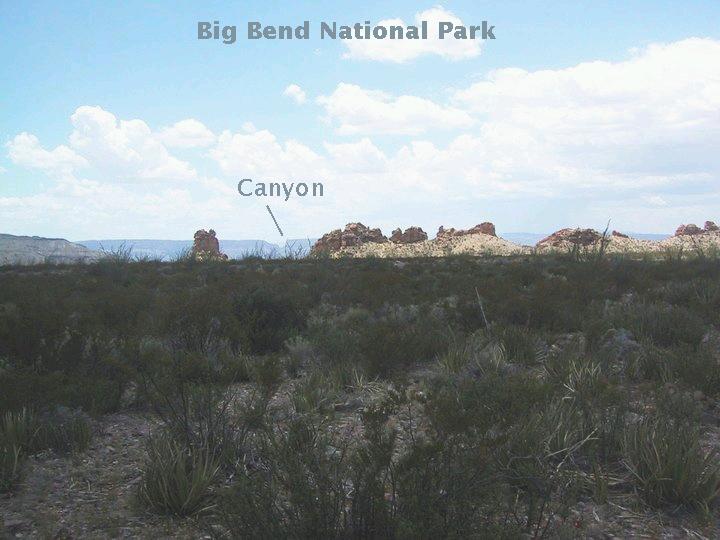

The next three images are of the Chimneys. The gap in Mesa de Anguila (Sierra Ponce in Mexico) marks the eastern margin of Santa Elena Canyon. The Big Bend website says the Chimneys are a volcanic dike (or at least did at one time; I couldn't find any information on the site at the time of this current writing), whereas the book Big Bend Vistas by William MacLeod claims they are a row of volcanic necks This latter interpretation seems unlikely to me. On the other hand neither interpretation explains the stratification that seems to be present in these outcrops. The circular accompanying the new USGS map, Scientific Investigations Map 3142, unfortunately has nothing to say about the Chimneys, but the map itself claims they consist of the Mule Ear Spring Tuff member of the Chisos Formation. So, I speculate they are neither remnants of a dike nor of volcanic necks, but just a particularly weather-resistant line of rocks. That would explain the stratification

The premier attraction of the Chimneys is the display of Native American petroglyphs. The image below shows the pillar of rock on which petroglyphs were inscribed.

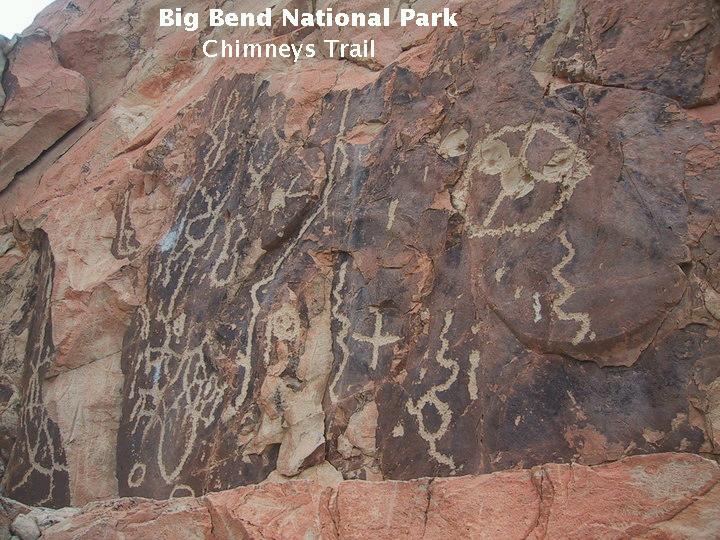

The picture below is a close-up of the petroglyphs. I'm sure archeologists would find meaning in these, but how do they know they weren't made by Native Americans bored out of their skulls? After all, what can you do in the desert for fun? Well, if you have a gun, target practice using the petroglyphs might be one possibility. Note the circular petroglyph toward the upper right, riddled with bullet marks. One can imagine drunken cowboys, also bored out of their skulls, taking potshots at it. Now, whether or not this is desecration, depends on when it was done. If it was done long enough in the past, it would now be history (although I'm not sure the cowboy contribution is old enough). On the other hand, inscribing your initials in the fireplace of the historic Homer Wilson Ranch headquarters, as we witnessed on a backpacking trip along the Dodson Trail, is definitely desecration. However, the worst desecration was probably the decision of the first managers of the park to tear down everything the settlers had built, essentially destroying that era of Big Bend history. The ranch headquarters exists only because it was built so well. The Wilson homestead below the Window is completely gone (although the daughter of Homer Wilson wrote that she found a leftover nail years later and kept it).

To the southwest of the Chimneys is Bee Mountain with beds of Chisos Formation members showing as outcrops below the not-so-well-studied trachyte volcanic rocks. Also note Santa Elena Canyon to the right. Trachyte is similar to the trachyandesite discussed above but has more silica. Below the trachyte is the 33 to 34 million year old Bee Mountain Basalt and the 44 to 47 million year old Alamo Creek Basalt, both members of the Chisos Formation. The trachyte on Bee Mountain is about 30 million years old. There is a radiometric age for the Bee Mountain Basalt here: 34.0 million years. Other Chisos rocks, uncharacterized, are present as beds on the mountain as well (Tcy). Geologists in the field find it difficult to tell the Alamo Creek Basalt and the Bee Mountain Basalt apart, so radiometric dates are very helpful.

The following view is looking west from the Chimneys. In the distance are the high Chisos Mountains, Carousel Mountain, and Elephant Tusk (an igneous intrusion). Between Carousel Mountain and the high Chisos lie the Sierra Quemada (Burned Mountains). Carousel Mountain overlooks the ranch house of pioneer rancher, Homer Wilson.

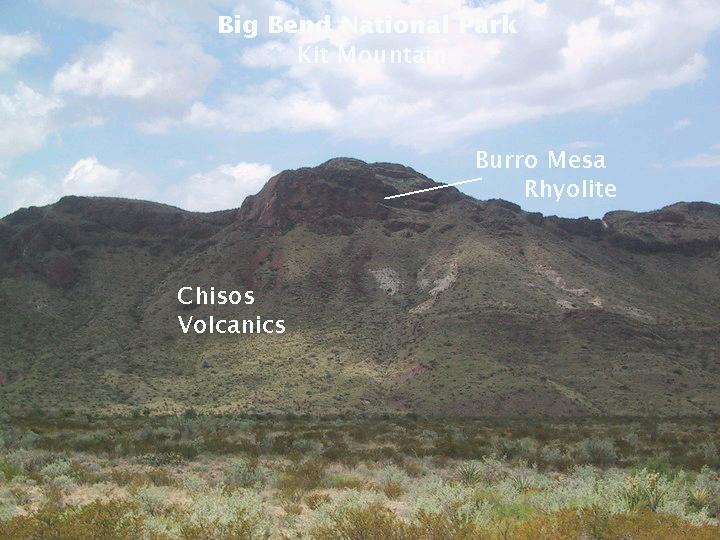

Your constant companion on the Chimneys trail is the east-west elongated Kit Mountain on your south, and it is time to take a look at this feature. In the image below you can see the bulk of the mountain consists of Chisos Formation volcanics (note the white volanic tuff) with a cap of Burro Mesa Rhyolite, the youngest member of the Burro Mesa Formation (29 million years young). Rhyolite is a volcanic rock high in silica, and tuff is hardened volcanic ash and/or other rock fragments produced by an explosive volcanic eruption.

On the west end of the mountain is a bit of an unusual feature, or at least so it seems to me. Behind the ridge in the foreground is a depression that apparently forms a dry lake bed. It appears this depression resulted from a landslide that may have been related to the presence of a fault that has been mapped to run along the northern border of the mountain. Most of the other material on the side of the mountain below the rhyolite is colluvium, a gravitational mass-wasting process that doesn't involve significant action by running water.

As you approach the trail head on your way back, you get a great view of the layer-cake stratigraphy of Goat Mountain (below). You can clearly see the volcanic strata that have been unveiled by differential erosion. The dark strata at the bottom of the mountain belong to the Bee Mountain Basalt. Above that are Chisos volcanics, including the Mule Ear Spring Tuff. I could not differentiate the Mule Ear Spring Tuff member of the Chisos Formation from the other Chisos rock. A radiometric date here puts the Mule Ear Spring Tuff at 33.65 million years of age. Trachyandesite appears above those units. This rock has been discussed previously, but it can be added that it is of intermediate iron composition between basalt (iron rich) and rhyolite (iron poor) like andesite but, again, with enhanced concentrations of alkali metals such as sodium and potassium. Since the alkali-metal feldspar that solidifies out of the magma takes up a lot of silica, trachyandesite typically has little or no quartz, which is the last common mineral to solidify. This unit used to be identified as the 33 million-year-old Tule Trachyandesite, but it has now been shown to be three million years younger. A radiometric date obtained from the rock here puts it at 30.3 million years old. At the top are the two members of the Burro Mesa Formation: the Wasp Spring Tuff and the Burro Mesa Rhyolite. Ages obtained for the Wasp Spring in the park range from 29.3 to 29.4 million years. The rhyolite was dated at this location and is 29.35 million years old.

FORWARD to the Window

BACKWARD to the Lost Mine Trail

ALL THE WAY BACK to the Contents